Dr. Brian J. Klebig

2021 Synod Convention Essay

Introduction

God has afforded us some unique opportunities for reflection in the form of the repeated traumas we have endured over the past year. I don’t use the word “trauma” lightly. Take a moment to consider that everything—from our basic interpersonal relationships with laity, to our corporate practice of the conduct of worship, to the composition of our leadership at its highest levels—has experienced upheavals that were swift, startling, and severe. Reflecting upon these ordeals will inform what we reflect to the world.

And this is why the sufferings of the past year are opportunities rather than catastrophes. We have experienced to a great degree the traumas of the world we seek to save. Our fellow humans have likewise experienced turmoil in their interpersonal relationships, their corporate structures, and their leadership over the past year. God gave Solomon more of everything that anyone could want; money, achievements, sex, wisdom, respect, power; so that when he said it was all meaningless we could take that to the bank. God gave Job more suffering; the loss of wife, children, friends, property, health; so that when he turned to God in hope we could know with certainty nothing can tear us away from our Lord. God has given the Evangelical Lutheran Synod a year in which we have experienced in extremes the same events that have influenced our world, while still maintaining His injunction to us: “Go.”

The future of pastoral care will be informed in both the short term and the long term by these events and other changes taking place in the world around us. Our challenge and our privilege will be to take the disasters of our past year and use them to ramp things up rather than wrap things up. God has placed us in a position where we can find triumph in trauma.

Accordingly, although it would be easier and far more tempting to focus on the negative impacts and sacrifices the upcoming communication environments demand of us, this particular work will focus more acutely on the ways in which we may maneuver within and understand these environments.

As a starting point for our considerations I propose three areas, all centered around the communication of the message at various levels. First, we’ll consider the technological landscape. The ELS occupies a position in a grand narrative of the communication of the gospel, and by situating ourselves within that narrative we may find greater clarity on what to pursue. Next, we’ll consider how the communication environment is likely to change the manner in which humans consume information. What changes can we expect to take place in what it means to be a human being in the coming years? Finally, we’ll consider ourselves and the shape that our ELS is likely to take in the coming years, which will inform our relationships with one another. Part of the power of pastoral care comes from the network of faithful men we are connected to through our synod, and the nature of that system and its future is worthy of serious attention.

Utilization of Emergent Communication Technology

The rate at which technological advances occur in the modern day is intimidating. New mediums are obsolete, overhauled, or outmoded before we have time to adequately consider their ramifications or develop the capacity to utilize them. What nascent advances in communication technology present the greatest opportunities to the continuation and expansion of our work in the future?

As is usually the case, a look at what came before is the best way to determine what comes next. In this case, let’s start by considering our distant past and take it all the way back to slavery in Egypt and position ourselves in the running of years that is the story of God’s Church on earth. Specifically, let’s consider how God has maneuvered His Church in conjunction with its mission to save the world through the communication of His Word.

The Children of Israel were sojourning in Egypt during a critical time in the history of communication: writing had been formalized, codified, and was being spread. During the time of the Middle Kingdom in Egypt a supremely limited number of people were literate, and the majority of the world’s literate population was confined to Egypt. Egyptian priests and aristocrats would have made up almost the entirety of mankind that could read and write. It is here that we see the hand of God working to not only preserve His people, but also to preserve and spread His message of salvation. Moses was raised in a noble Egyptian household and would have had the capacity to utilize this fairly new communication technology of writing. No sooner were the Chosen People out of Egypt than God made use of Moses’s special skill in recording the Law and through this invention of writing giving mankind its mirror, curb, and guide.

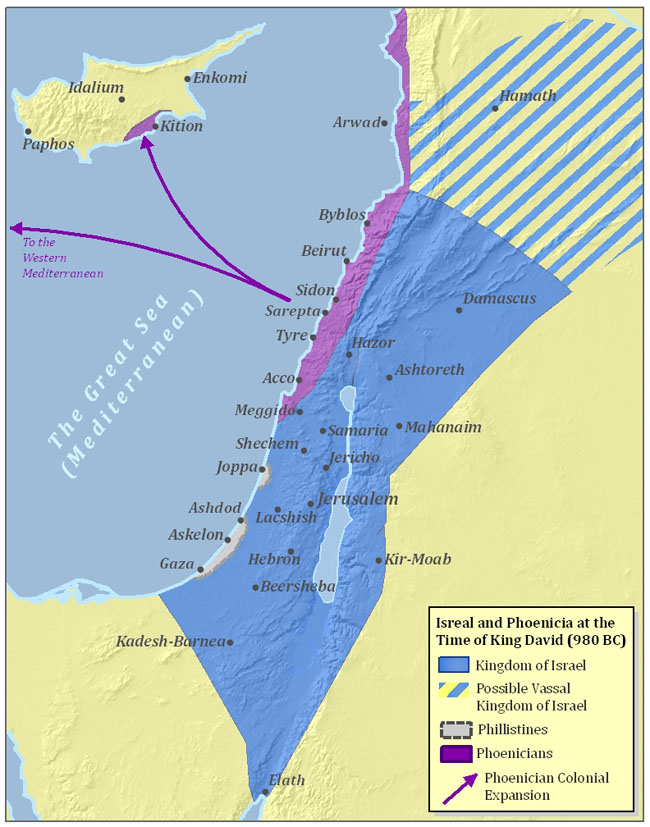

The nation of Israel carries these commandments into the Promised Land, where God instructs them to wipe the inhabitants out. It is notable, then, that one nation dwelling in the Land, was omitted from God’s instruction to drive away. The nation of Phoenicia based its maritime trade empire from this area. This group’s presence in the Land was undeniable: they were completely intermingled.

And yet, the Phoenicians and Israelites lived together in peace for the duration of their kingdoms. Over that time the Phoenicians contributed material to the building of the temple, sailors to Solomon’s fleets, armies in every conflict the Israelites faced, and most importantly their inventions.

Near the time of the arrival of the Children of Israel to the Promised Land, the Phoenicians developed a new revolution in communication to assist with their international maritime trading empire: a phonetic alphabet. Because the Phoenicians needed to deal with so many different lands, each with their own languages, many with their own systems of hieroglyphic writing containing thousands of characters, they simplified the process by crafting an alphabet where characters would represent sounds. The alphabet of the Phoenicians is identical to that of the Israelites with the exception of just one sound (ש or “shin,” which is part of the reason why that letter appears twice in the Hebrew alphabet with just a dot to distinguish it, but we digress).

So once again we see that God positioned His Church in a place where a massive communication advance was taking place AS it was taking place. The Israelites were the first beneficiaries of this innovation which allowed for expansion in literacy and ease of transmission, even between cultures.

Following Jesus’ death, a challenging injunction was given to the disciples: they were to spread the Word throughout the world. This challenge was compounded by the fact that the canon had yet to be assembled. Letters, writings, and accounts began to spread through the newborn Christian Church, but assembling them together and definitively stating, “These are the words of the Lord” was a challenge. At the same time that the canon was being assembled, a tremendous technological innovation was being developed at the Church’s center in Rome.1 Scrolls are a huge pain to search through, and Romans were fans of lists, references, and systematics. To make life easier they developed a medium that could be easily searched through, or “paged” through: the codex. This made cross-referencing, checking, and making connections far easier, just as the Bible took shape. God again positioned His Church at the center of a communication revolution.

Of course, the one we’re maybe most familiar with, Gutenberg’s printing press, was still a relatively new innovation just as Luther was nailing his 95 Theses to the castle church doors in Wittenberg. The writings of the Reformation, printed and carried throughout Europe, brought the Word of God to millions who, despite having been raised calling themselves “Christians,” had never known of Jesus’s love and forgiveness.

Even minor advances in communication coincide with events in church history which experienced outsized benefit from these achievements. For example, between about 1520 to 1539, Hernando Colon (Ferdinand Columbus), the son of Christopher Columbus, invented cataloging as we know it, the practice of stacking books sideways instead of laying them flat, and “Cliff’s Notes” summaries of books. These advances made literature much more searchable, understandable, and accessible, just as the Reformation was making that case that everyone should be able to read and understand the Bible. Doctrinal treatises were written by authors like Chemnitz, repairing the broken theology of Rome via a lengthy series of investigations rooted in Scripture, while dedicated translators like Petri made the Bible itself accessible to everyone.

Certainly while the gospel has dwelt in North America we’ve been at the forefront of multiple advances in communication technology. Radio was a critical tool in spreading the gospel to distant lands and to every ear. My own grandmother, raised in an atheistic household, heard the gospel and came to faith in her teens listening to a broadcast of the Lutheran Hour. I think it’s difficult to make an argument that Christians utilized television and film to their full potential, and certainly accidents of the mediums themselves made them more difficult to employ, but even these communication monsters are now receding or mutating into new media.

Each advance along the way came with advantages and sacrifices, and were equally celebrated and mourned by the people of the time. The myth of Thamus and Theuth (Thoth), for example, represents an argument between the false god of knowledge, Theuth, and a particularly wise Pharaoh, Thamus (Plato, 1952). Theuth presents the king with writing and is very excited about it, talking about how it will improve human memory and grant far greater wisdom.

Thamus is not impressed. He points out that since humans won’t have to rely on their memories anymore they will get weaker, not stronger. Furthermore, people will use the writings of their forebears in order to build knowledge upon rather than discovering that knowledge for themselves, and thereby have only the accidents of wisdom rather than actual wisdom.

Thamus was not wrong. It would be a mistake for us to discard writing on the basis of these sacrifices, but it would also be a mistake for us to fail to acknowledge that sacrifices of ourselves were made. This technological innovation of writing made human beings weaker. It was a sacrifice made of ourselves for an advantage granted by a piece of equipment. The myth sets a solid pattern for how we best approach innovations today: with an appreciation of the advantages they pose and a conscious effort to mitigate, or at least understand, the losses they impose.

Beyond that, we should acknowledge that as communication landscapes change, humans change. As Thamus predicted, our memories are indeed worse than our ancestors’. This is a consequence of centuries of relying on written documents. I have heard it often observed (never positively) that the attention spans of youth have gotten very short. The evidence backing this assertion up is pretty terrible; attention is highly variable and task-specific. Consider binge-watching, for example. Comedian Andy Woodhull, talking about his two daughters, said, “This is going to sound ridiculous to the young people in the room, but it took me ten years to watch every episode of Friends. My girls knocked that out in a weekend.” (Woodhull, 2019). Clearly humans retain the ability to isolate and dwell on a single topic for extended periods of time. However, I think we can say with confidence that our expectations concerning how we consume information lend themselves toward more rapid-fire presentations. Television shows are shorter than movies. Their cuts are faster. YouTube videos are shorter than television shows. Editing practices that would never fly on TV, such as jump cuts, are widespread on YouTube to enhance the image of information being delivered extremely quickly.

The apparent reduction of attention span now seems to be driven by the sheer quantity of information that users have access to. Less attention is dedicated to any given message because there are multiple other messages that a person may be attending to which may augment and enhance the content of a single communication. I have to confess that over COVID’s lockdown I was once able to attend two meetings and my buddy’s transfer of command ceremony simultaneously while setting up to guest preach out of state. Was this optimal for either of the meetings I was in? Of course not! Was my partial attention and attendance preferable to none at all? Almost certainly.

As we bemoan the disadvantages imposed by media advances, we should also seek out the advantages. As we bemoan the changes in human beings as a consequence of media advances, we should also seek to reach them as they are and not as they would have been decades ago. My grandmother became a Christian when she heard the gospel on the radio. She had six children. Two of them became pastors. She has almost forty grandchildren, almost all active in their churches and ministries. That radio broadcast had a significant impact for me personally and for the work of the Kingdom. The grandmothers of tomorrow are today’s irritating teenagers, stuck on their cell phones, earbuds permanently blasting terrible music, with attention spans shorter than heavily caffeinated squirrels. Is it annoying to us? Absolutely! Does it put us on our heels? Definitely. Is it something that is to our advantage to consider seriously and work with? Yes.

It is easy to mourn the loss of what people used to be, and indeed most generations have identified that their offspring are themselves somewhat weaker and yet more advantaged than they were. But King Canute might well advise us to remember our call to communicate the gospel to the world, with the confidence that the Holy Spirit moves and works faith through that message, no matter the era in which it is communicated.

It behooves us, therefore, to consider what we gain and what we sacrifice with these mediums, maximize the benefits, and, so far as is reasonable within the context of our calls, mitigate the losses. This will also allow us to consider what the future may hold in store for us and how we communicate the message of salvation. Accordingly, rather than look at specific communication devices that are likely to come along (an interesting topic in itself), the best way we can prepare for future communication environments is to consider what people will be like in the future, most often as a consequence of those communication technologies.

The most notable influence on what people will be like are the recent events which have pushed us into a world where (tele)presence is particularly crucial. The past year was spent reliant upon synchronous communication technologies such as streaming and virtual meeting platforms in order to continue to operate, as well as asynchronous recordings of study material and devotions. Undeniably these technologies have involved substantial sacrifices, however they also provided avenues by which we could continue to operate in these unusual circumstances. As the world shifts toward its previous method of operation, it is unlikely that the necessity of these technologies will disappear, nor will our parishioners’ expectations concerning them. Consequently, we can expect that certain population changes will occur in the coming years.

Considerations For Our Changing Communication Environments

Illocality

There is a tremendous benefit to being somewhere without being there. I attended church from home for about half of 2020, as did most of our people. Now, the wording that is chosen in that sentence is immediately unusual: I “attended” church from home. I don’t consider my home a church, even though religious activities occur there. I also don’t believe that my house became a church by virtue of the fact that I had the service on the television or, more interestingly, on my virtual reality headset. However, I still had a sense of being “at” church, even though physically I wasn’t.

This extension of self to a remote location via a mediated connection is sometimes referred to in communication circles as (tele)presence. The idea is that, as we become increasingly involved in the situation we are viewing, the media that divide us start to disappear and gradually we have a sensation of being in a different space. It’s not terribly different from the sensation of transportation that one might encounter reading a book. Accordingly, far before this past year, we were already becoming acclimated to the idea that, while we may be physically present in one place, we might be remotely present elsewhere, even in places that are not real. Film and television got us to accept the reality of these mediated spaces, while video games and the Internet gave us the expectation of being able to interact and be “present” in those spaces via a digital avatar. Some confessional churches have, over the past decades, taken the enormous step of broadcasting their services on television, and we owe them serious kudos. I’ve spoken to many about why they absorbed the time and expense, and the answer was typically that it allowed them to serve their elderly population better.

Over the past year, the entire country has had to adjust to an idea of being remotely present, and although it involves many sacrifices and tradeoffs, at this juncture, it seems that people would be reticent to let it go.

What does this mean?

2020 has produced certain realities in the majority of our churches. First: the dramatic majority of our churches now possess the infrastructure necessary to facilitate remote attendance. Second: both our laity and the people we hope to reach in our communities have an expectation that they will be able to interact with their churches remotely.

These realities can be viewed negatively as many elements of remote worship are undesirable. However, they also present some opportunities that we would be remiss to not exploit. First, and most obviously, the infrastructure that has been developed to facilitate divine services over the Internet can be utilized to support other programs in which locality may be a barrier to attendance. In particular mid-week Bible Studies, special topic presentations, and specialized activities might benefit from affording participants the option to attend from a distance. Certain populations experience an outsized benefit from this improved access. Most apparent amongst these groups are the elderly and those with mobility issues. Parents with small children are also strong beneficiaries, since arranging babysitting often presents a substantial barrier to attending special functions. A potentially surprising population that benefits are the unchurched. Depending on your area, getting someone to attend an event on church grounds, even one with no obvious theological purpose, can be a challenge. The additional step of removal from attending remotely can clear a barrier to access without involving overmuch sacrifice, since the power is ultimately in the Word.

Second, certain functions of the church are easier to accomplish online. Coordination, management, and planning can benefit from having more widespread access. Consider, for example, the number of meetings you have attended in the past where someone has guaranteed they would accomplish a simple task when they got home and had access to the necessary equipment. Access to necessary resources can make meeting illocally extremely beneficial, particularly when the meetings are planned with that access in mind.

Additionally, aspects of the conduct of the service itself can benefit from an illocal environment. In particular, inviting others to attend worship is much easier online. There are a large number of free apps that allow for viewers of online services to invite others to attend, even to the point of dropping the event into their calendars. To be clear, the main perceived benefit from this advance is actually an illusion. One might believe that a person invited online is more likely to attend, since it removes a barrier, however there is no evidence to support this and, in fact, it is far more likely that the opposite is the case. Already the chances of an unchurched person accepting an invitation (via direct appeal) from a friend or family member were likely somewhere between 65 and 81 percent (Lifeway, 2011).

The actual benefit goes more to our members. Being able to invite someone online removes barriers for a member actually inviting someone. It leverages the advantage of illocality that, while they are in the service and feeling most motivated, they can immediately act on that motivation and reach out to someone they know. The 65–81 percent chance of acceptance via direct appeal is meaningless if nobody ever invites anyone else to church, and sadly this is often the case (Barna, 2018). The problem then is not barriers to acceptance but barriers to invitation, which the illocal nature of a mediated divine service mitigates. In turn, this helps the pastor with one of the more challenging aspects of our care for our parishes: the mobilization and motivation of the laity. Getting someone started with the easiest form of evangelism renders it more salient in their minds, making it more likely to occur in other, non-mediated settings as well (Higgins, 1996).

Furthermore, just as meetings can benefit from having materials at hand, so too a divine service might benefit from having improved access to study materials, however we will discuss this at greater length later.

One final thought on illocality: we see in general the receding of the importance of physical structures. That’s why we don’t see so many skyscrapers being built, and those that already exist sit empty. It is why department stores are closing left and right. It is why most malls are largely empty. Not only are we able to do more from home, we are now accustomed to doing more from home. We should consider strongly, then, the role that we intend for our physical church structures to fill, particularly as elements of their functionality are able to be moved out of the building. Building an atmosphere of the church as a central location for a person’s faith life can offer significant blessings to both the church and the people it serves. Obviously this isn’t to suggest that physical church buildings should be consigned to history, but their relevance for a parishioner might shift. Within the concept of (tele)presence there are some sub-categories, like social presence, which are especially worth considering.

Social Presence

While togetherness is not the central focus of the divine service, I think most of the people in this room would agree that it is the thing that was most widely missed by our congregations. This makes sense, believers gathering together is an integral part of being a believer in the first place. Participatory worship, for example, is a significant part of our heritage, but is not natural to environments like streaming (a one-way communication) or even nearly synchronous environments like Zoom.2 I started asking my students whether they would do responses when worshiping from home. A few of them said their families tried, awkwardly, but that it went away within a service or two and they switched to watching. I only had one student say that his father insisted on them doing responses in the home, but that it ended up causing him to really question his faith because he started to wonder if he was, in fact, in a cult. Obviously, the cultish vibe is not something we are shooting for with participatory worship, so it begs the question: what is missing from the experience that made it feel that way?

The sensation of being with other people in a mediated environment is that aforementioned sense of social presence. We could replicate the church building, we could replicate the sermon, delivering it to an empty room but hoping the camera would transmit that message via streaming into many living rooms. But at the end of the day the people were missing. Accordingly, there was a low sense of involvement in the service (which is objectively accurate, since they were typically delivered in a one-way communication), and a sense of lack in their connectedness to others. Even large-scale, personal connection programs, like Zoom, in which participants can be seen and heard synchronously, suffer from a lack of social presence. As a professor I can certainly attest that the attention and involvement of students who were not present in the classroom was noticeably diminished. Beyond that, an integral part of pastoral care is having an idea of the level of involvement from various members. This is difficult to achieve when a sizable portion of our congregations are attending but not physically present.

Was ist das?

Relationships are still foundational to the operation of a church. In mediated environments, we need to seek out means for communicating as directly as possible with remote participants. The first thing required is the means to make this connection. At present there are a few free and easy options which, while highly imperfect, at least provide a starting point. Chat features, group VoIPs like Discord, even directly connecting via messenger services or text can be a way to cross the gap.

The second required element is far more difficult: our time and attention to make those connections. Pastors need to be where their people are for a two-way conversation, and if the people are online, that’s where the pastor’s interpersonal interactions should be. It may be beneficial to take some of the time that we spend before and after a service engaging with people who are attending online. This will dramatically increase their sense of involvement and social presence, which will enhance the overall experience. Additionally, it allows the pastor to stay plugged in to the lives of the congregation, remain aware of their struggles and successes, and accordingly know where the Word can be most beneficially applied on an individual basis.

You may have noticed already that the currently available technologies for enhancing a sense of presence, for lack of a more academic word, stink. The expectation would be that technology will move in a direction to attempt to fill this need, and indeed when we look at the current communication development trends that is what we see. Social presence is one area in particular where emergent technologies may be of extreme use. Our organization is not the only one to have been negatively impacted by a lack of social presence in our remote gatherings. Many of the nascent technological innovations are designed around directly dealing with this difficulty. We can anticipate that as virtual reality (VR) and mixed reality (MR) continue to diffuse, expectations concerning a sense of social presence at mediated gatherings will grow. The quality of VR environments is already astonishing and it continues to improve, with a sense that objects and people are actually there.3 Pastors and evangelists should position themselves where the people are in order to communicate the gospel message, and these mediated but still social environments will likely be key to forming and maintaining some of those relationships.

On a more practical, directly applicable level, there are even now some augmented reality (AR) apps for smart phones that could achieve this same sense in an asynchronous fashion. For example, it would be entirely possible to use a smart phone now to insert a three-dimensional, virtual image of a pastor into a church, positioned up at front, and leading a Bible Study or prayer. These programs could provide the church greater functionality as a more frequent hub of an individual’s spiritual life, rather than a Sunday morning and Lenten midweek destination.4

It is reasonable to expect that, as digital environments and objects become mainstream, there will be a decrease in the value that people put on physical objects, potentially even on physical togetherness. Consider the record industry when MP3s came out for an example of this effect. Since digital replication is easy, free, and high quality, there was very little reason to purchase physical media, and accordingly the value decreased and other means of monetization had to be pursued. Now consider that same scenario, only instead of what we hear it is what we see. The ability to put a painting on my wall without having to buy, frame, hang, and level it poses a lot of advantages. For as problematic as this may be, it would be negligent to not consider advantages to our mission in terms of the transmission of the message, access, and costs, and then seek to maximize them.

Particularly important to this sense of social presence is two-way information flow and interactivity, which also dovetails with another expectation we can have for our people in the future.

Divided Attention

While most might identify a reduction in attention spans, I would suggest that it is more likely that people will have more divided attention. That old stereotype of an individual, fixated on their television with a little bit of drool dribbling from the corner of their mouth, is almost entirely annihilated. Very few people will engage in only one activity (Dumont et al., 2008). Even now I am willing to gamble while writing this that when it is being delivered at Synod Convention BORAMs are being skimmed through, text messages exchanged, emails received and sent, side conversations had, etc. People are probably driving while listening to this, a punishment for presenting on Wednesday of the convention. Now, undoubtedly this gathering represents an outlier in which more people will be cheerfully reading along with a spoken manuscript than the mean population would. Accordingly, I suppose I could become angry about the distractions and demand more rapt attention from participants. Except I’m not confident that this would be the best way to get more out of our gathering. Maybe something discussed rang a bell, maybe you googled “Streaming chat services” while we were talking about it. That’s certainly a distraction, and distractions negatively impact productivity, but it’s a distraction I would welcome and encourage.

Individuals will be more inclined to split their attention between multiple sources, and might even become anxious when they are unable to do so (Wang & Tchernev, 2012). This practice trades cognitive needs for emotional ones. In other words, when attention is divided our cognitive acuity drops but we enjoy ourselves more. Specifically, we become less bored when our attention is divided (Tze, Daniels, & Klassen, 2016).

It seems we have a terrible decision to make between a person’s ability to retain information and their motivation to do so. However, we would expect that while people may become more prone to boredom, their perception of what constitutes a boring activity is also susceptible to easy change (Hunter & Eastwood, 2021). In short, being accustomed to divided attention means that a person is willing to change their mind pretty quickly about what is boring and what is not, or what is worth paying attention to and what is not. The drivers for these perceptions are easy to influence, and we have the resources at hand to do so.

Quae est huius praecepti sententia?

While we might expect norms and standards of politeness to change (e.g., more people using cell phones during a service), there are aspects of divided attention that we can turn to our benefit. The church itself generally provides a lot of elements that can make good use of an individual’s divided attention and gain engagement. For example, many of our churches have Bibles in the pews. Calling on the congregation to grab the Bible and look at something, especially for establishing context, can provide an extra information stream without putting so many cognitive demands on a person that they have split attention. Other strategies which allow a person to either take in more sensory data, shift focus from one sense to another, or allow them a level of activity are already necessary practices and will likely become even more critical in the coming years.

It is likely that we will face more “is this going to be on the test” moments as well. We should consciously employ linguistic and rhetorical devices to deliberately call attention to the most important portions of a sermon. Something as quick and easy as simple repetition can cue a person to pay attention, and with the expectation that our congregation’s attention will be divided, these cues become all the more important. I highly recommend Rev. Matthew Moldstad’s and Rev. Tom Kuster’s recent papers at GPPC as resources in this specific regard.

Death by a Thousand Cuts

Really, for us this can be “Death by a Thousand 5 Minute Tasks.” A pastor’s schedule is already bloated beyond what can be filled by him as an individual. This is not a new problem, but it is a problem which is presently being compounded. The ability to engage in multiple activities simultaneously invites more activities even as it also invites more distractions. There’s some research to suggest that it takes about 15 minutes to get back into a groove after getting distracted, but we are surrounded by 30,000 distractions all the time. At the same time, injunctions, even like the ones in this paper, are constantly being added to us. Now it’s not good enough to have done the job we trained for, now we have to be doing evangelism in VR and managing our online presence? There is not sufficient time. Smart homes have already been attempting to deal with this problem for a little while, by simply removing smaller, more menial tasks from our to do list. Similar solutions are likely to appear in churches.

What does this mean?

We have two real avenues for reducing the burdens on a pastor’s time. The first avenue is to delegate. This has always been considered a great virtue, but one that not everyone possesses. However, as our schedules constrict us to an ever-greater degree, sometimes even impinging on those things which we must get done, the importance of finding help becomes increasingly apparent. Taking an opportunity to bring help in on some of our traditional functions can be a massive relief. For example, musical selection and the conduct of the liturgy can sometimes get short shrift, but a worship coordinator can help give it the attention it deserves and bring out its importance and beauty for a congregation.

There is, however, a second avenue, and that is to automate. Church buildings are fairly complex entities. We can expect that smart devices such as lights, locks, temperature controls, and electronics will have continued advances in automation, and become cheaper as they do. Beyond that, some service aspects of the church may require less manpower as a result of automation. The changing of opportunities for service is something to keep on the radar as maintenance tasks become increasingly automated. Rather than be caught flat-footed, as much of the corporate world was by automation reducing labor needs, we should consider now how best to direct parishioners for Christian service.

Structural Change

This is a snapshot of the clergy of the ELS in 1925,

and here again in 1963

and finally a recent one from 2016.

Each of these images captures us a synod, and pictures are useful because they reveal things. When we look at these we see changes, some of those changes can be very meaningful.

However, at the end of the day these are just snapshots of people, faces, clothes, and other visual trappings. Looking at changes over time in these pictures is a bit like saying that the difference between the ELS and Baptists is that we don’t baptize by immersion. That’s technically partly true, but pretty superficial. If someone was sick the day of the 1963 picture and had someone put black, horn-rimmed glasses on to cover for him, would we even know? If we did know, would we care? It wouldn’t change anything.

But what if we could take a different snapshot that did more than simply capture the outside, but also what was happening beneath the surface? What about a picture that shows the things that bind us together, and captures the unique way in which we relate to one another? It may tell us some very interesting stories that would otherwise be very difficult to ascertain.

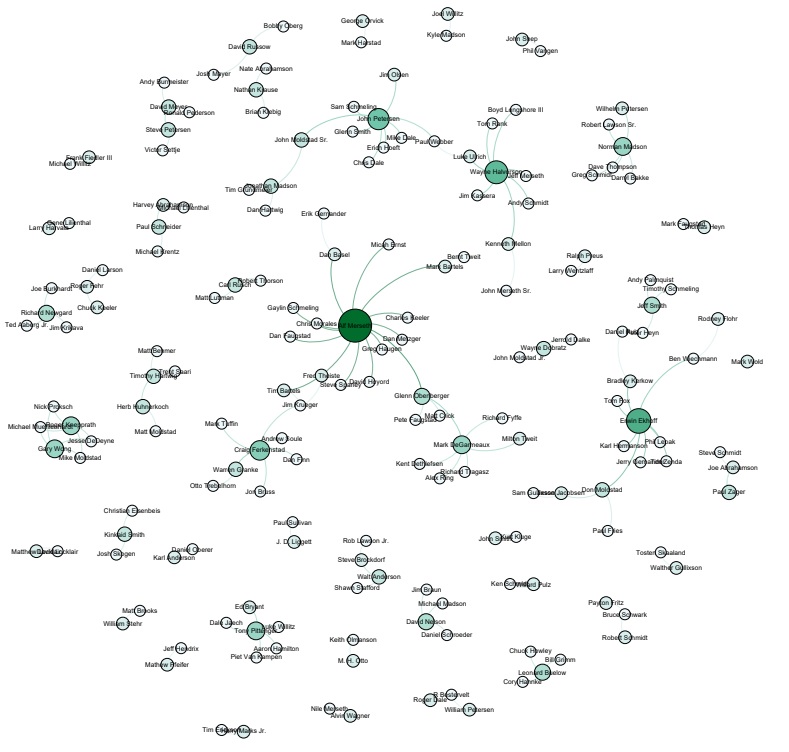

One relevant image may be a snapshot of the formal mentoring relationships we have, namely our vicars and their bishops.

Fig. 2 is a network map of the bishop and vicar relationships in the ELS. Every dot is a pastor, every line is a bishop/vicar relationship. The bigger and darker the dot on the network map, the more vicars that particular pastor has trained. We can gain a little more understanding when we look at some of these relationships. We can see lots of happy stories, deep connections, a few sad stories, thought lines, attitudes, and heritages that stretch back through generations.

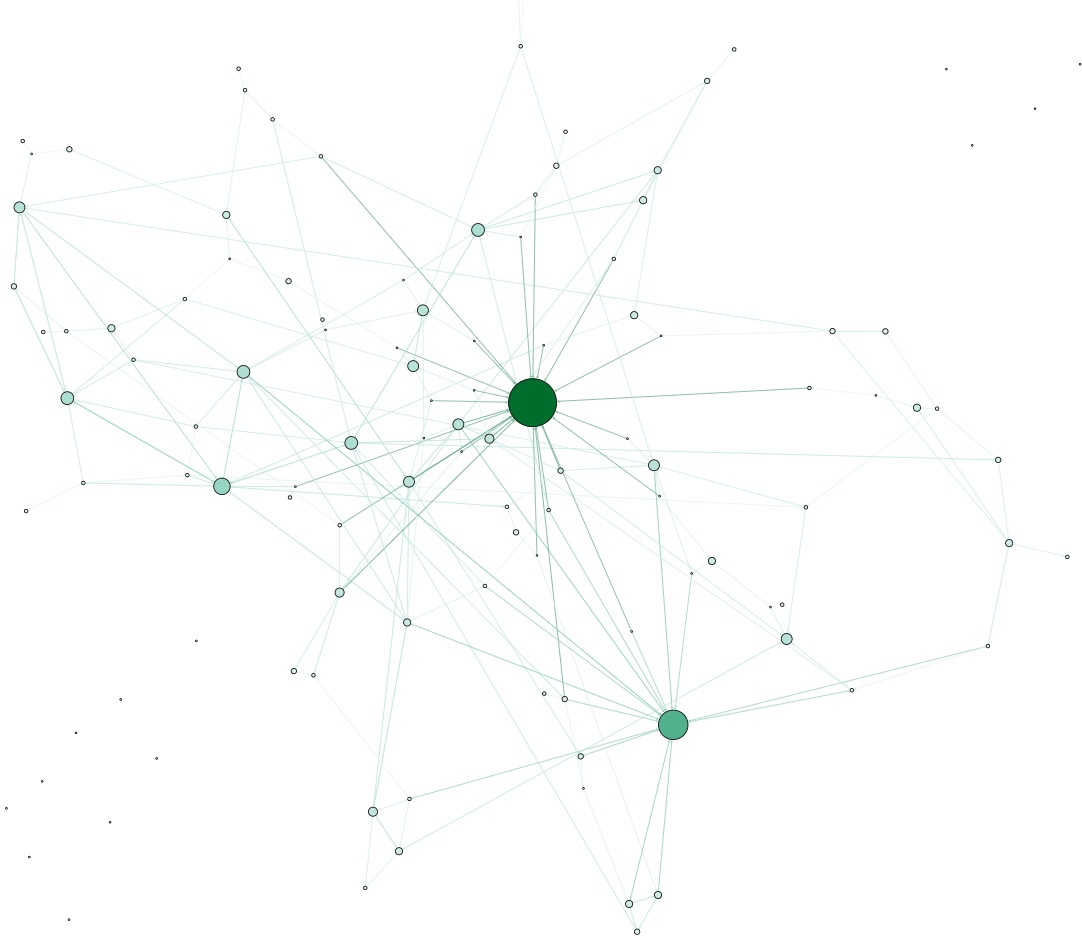

Figure 3 gives us another one of those internal pictures. This one is a map of the salient information channels in the ELS. Many of you may remember that I had URAs contact you to ask who you looked to for advice concerning your ministry, and this is the resulting data. It tells us some pretty interesting stories and is instructive for what our futures likely hold, but in our present circumstances one consideration is elevated beyond the others.

The names for the dots are not featured, and before you ask I am afraid I have no idea which dot is yours. In point of fact I don’t know which dot is mine! However, I do know the identity of the big one in the middle. You might be able to guess just from looking at the system who it belongs to: that dot is John Moldstad’s.

We are already united in the paradoxical Christian response of grief and celebration when confronted with death, but this map reveals the true scale of the loss to our earthly organization. Looking at this chart we see that President Moldstad was more than an administrator, mentor, and elected officer. He was a conduit through which we had personal relationships with one another. Because of John we were only ever a couple of degrees away from even the most remote of our brothers in the ELS.

A significant part of pastoral care is this interconnectedness that we have with one another. The loss of John to this system weakens the relationship bonds that help hold it together, and this can adversely influence our decision making. Organizational communication studies have indicated that increased stress, more serious conflict, greater institutional attrition, and reduced productivity are all likely consequences following the sudden death of a leader (Farquhar, 1994; Farquhar, 1995). Looking at the map we can see why. The closeness of the relationships helps quite a bit with making the 8th Commandment a little easier to follow, because the proximity is so tight. With no John that distance increases and we have less extrinsic motivation to extend the benefit of doubt or take someone’s words and actions in the kindest possible way. Perceived slights that once may have been ignored, conflicts that may have been mitigated, opposing parties that could have been brought meaningfully to the same table, now are all less likely to resolve amicably. The abrupt nature of John’s death further compounds the damage, as there was no opportunity to brace, develop systems to deal with the loss, transfer these connections meaningfully to a successor, etc. (Norbash, 2017).

For our immediate future we should recognize the scope of the loss we have endured and watch for its effects in ourselves. This Synod Convention is perhaps one of the more important ones we will have in our lifetimes. Our relationship structure was already badly frayed as a result of COVID-19. And now our connections with one another have taken the most pronounced hit that they can on an organizational level. While there is no existential doctrinal crisis demanding our action or lions clawing at the gym doors, we face a critical dearth in our connections to one another. I think there’s a priority for our gathering this year: that we make time for friendly relationship building with each other. However, we should also recognize that our efforts will not be able to fully mitigate the impact of this loss, we should expect some short-term turmoil, and if we err in our judgments we should err on the side of grace.

Let’s expand a little bit on the above structure, because this was actually the predicted shape that this system would take. There are natural dividing points in how humans gather and the patterns of relationships change according to the size of those organizations. The primary dividing line is around 150, which is one of the reasons that, traditionally, it has been difficult to move a church past an average Sunday attendance of 150 until it would stabilize at about 225 (Martin, 2005). Social media outsources some of the brain’s responsibilities for maintaining a relationship, so we are likely to see that number increase, but the majority of our churches have an organizational structure very similar to the one we see in Fig. 3.

The pastor would typically occupy that central node for churches that see an average Sunday attendance between 75 and 150. While certainly not central to our decision making, nor a critical part of a call, it would be unwise to ignore the role that we play in the relationship structure of the churches we serve. As we move into an increasingly post-COVID world, the facilitating and building of these relationships should be a priority, and centered on the one thing needful.

Pastors are at the center of a relationship network that is united by faith. If other considerations begin to be featured at that central node, it will exert an influence to push people out of the system. Accordingly, it is well worth our while to avoid entanglements with external movements. Obvious contenders are political and cultural movements, which can really throw artificial barriers up, but even more subtle entanglements might be an issue. I remember a pastor on the West Coast whose office was filled with Green Bay Packer merch. To be clear, I do like the Packers. But what was surprising was that when I guest preached for him, I had more than one of the members comment on his continued attachment to Green Bay after more than a decade in their area.

Obviously we have personal convictions and allegiances, but bearing in mind our position in the congregations to which we are called, we should be mindful of who is aware of those positions, and under what circumstances they become aware of them.

Conclusion

The soul of the future of pastoral care will remain unchanged from how it has been done for two thousand years. We preach Christ crucified to the world. We encourage and assist our congregation members in their spiritual growth, holding Jesus’ cross in front of them as they go through life’s best times and life’s worst times. We gather with believers to receive forgiveness and to learn more about our relationship with God.

Just as the locations and means for accomplishing these objectives have changed consistently over the millennia, we expect them to continue to change in the future. Values on illocality, the ability to divide attention, and the chance to meaningfully connect with others digitally are now embedded in the people to whom we wish to minister. As technology continues to race along we should be mindful of how we can implement innovations to minister to the people of our own time.

This calls for consistent self-reflection, and an appreciation of what impacts our environments are having on us. However, it also calls for confidence and bravery, particularly in difficult times. Just as God has walked with His Church throughout its history of change, He walks with us now into the future. Paul’s exhortation to joy in II Corinthians 12 takes on a special relevance for us, because humanly speaking it would be easy to despair after the losses and threats we face, “But he said to me, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.’ Therefore I will boast all the more gladly about my weaknesses, so that Christ’s power may rest on me. That is why, for Christ’s sake, I delight in weaknesses, in insults, in hardships, in persecutions, in difficulties. For when I am weak, then I am strong.”

May the power of Christ rest on you throughout your futures.

References

Barna Research Group. (2018). Sharing Faith is Increasingly Optional to Christians. Faith and Christianity. https://www.barna.com/research/sharing-faith-increasingly-optional-christians/

Dumont, E., Fortin, B., Jacquemet, N., & Shearer, B. (2008). Physicians’ multitasking and incentives: Empirical evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of health economics, 27(6), 1436-1450.

Farquhar, K. (1994). The myth of the forever leader: Organizational recovery from broken leadership. Business Horizons, 37(5), 42-51.

Farquhar, K. W. (1995). Not just understudies: The dynamics of short‐term leadership. Human Resource Management, 34(1), 51-70.

Higgins, E. T. (1996). Activation: Accessibility, and salience. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles, 133-168.

Hunter, J. A., & Eastwood, J. D. (2021). Understanding the relation between boredom and academic performance in postsecondary students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(3), 499.

Lifeway. (2011). Churchgoers Believe in Sharing Faith, Most Never Do. Lifeway Research. https://lifewayresearch.com/2014/01/02/study-churchgoers-believe-in-sharing-faith-most-never-do/

Martin, K. (2005). Myth of the 200 Barrier: How to lead through transitional growth. Abingdon Press.

Norbash, A. (2017). Transitional leadership: leadership during times of transition, key principles, and considerations for success. Academic radiology, 24(6), 734-739.

Plato. (1952). Plato’s Phaedrus. Cambridge, University Press.

Tze, V. M., Daniels, L. M., & Klassen, R. M. (2016). Evaluating the relationship between boredom and academic outcomes: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 28(1), 119-144.

Wang, Z., & Tchernev, J. M. (2012). The “myth” of media multitasking: Reciprocal dynamics of media multitasking, personal needs, and gratifications. Journal of Communication, 62(3), 493-513.

Endnotes

1 Obviously Alexandria and Antioch are not to be overlooked during this time period, but bear in mind that one of the major drivers that caused Rome to become the eventual hub of Christianity was the fact that they so consistently fell on the correct side of doctrinal disputes in the early Church. I would suggest that a primary reason for this was the utilization of their new communication innovation.

2 As a side note, I’m not aware of any churches that used Zoom to conduct services, but if you did then I’d like to speak with you and pick your brain about how it worked. If you have some recordings then so much the better.

3 VR and MR present some excellent opportunities for gospel communication that are outside the purview of this work. The GOwM conferences, hosted by the CMI, have some works that consider the potential role of these environments in our future work. There is a serious need for real consideration of how to utilize these mediums and a need for encouragement of Christians to learn and operate them. Other exceedingly useful resources on everything from hymnody to outreach to app development can be found at gowm.org in the archived conferences.

4 Smart home technologies can be unbelievably useful in this regard. I’ve heard many pastors bemoaning the fact that they have to lock their churches up. It would be entirely reasonable to provide church access, or specific area access, via smart locks. This opens up possibilities for making the church much more widely accessible to serve as a place where people can pray, study, or gather to whatever degree the congregation feels comfortable.